This week, Tánaiste Micheál Martin spent the bones of four days in China, on a visit with all of the usual trappings: political meetings, speeches at universities and briefings with state agencies.

But his visit had something of an awkward prologue.

In May, in a major speech setting out Ireland's stance towards China, he said Ireland needed to be clear-eyed about China's goals – that the two countries had differing worldviews, interests and values.

"This reality will inevitably shape how we engage with one another," Mr Martin said.

The Tánaiste said Ireland and the EU needed to de-risk its relationship with China, but should not decouple from it.

"De-risking" and "decoupling", of course, are the awkward EU terms of art used to describe the need to reduce our reliance on China, while still continuing to trade.

As you can imagine, the response from the Chinese Embassy in Dublin was less than cheerful.

"Regrettably, the speech overexaggerated the differences between China and Ireland and emphasised the concept of 'de-risking' with China," it said in a statement.

Though he would deny it, the Tánaiste spent much of his trip softening the stance he outlined just a few months ago. And that meant he spent a lot of time explaining what de-risking actually means.

EU jargon, usually conceived with the best of intentions, has a penchant for being misunderstood. China is meant to be pleased that we only want to de-risk, and not decouple. As you may have gathered, that is not how it has gone down.

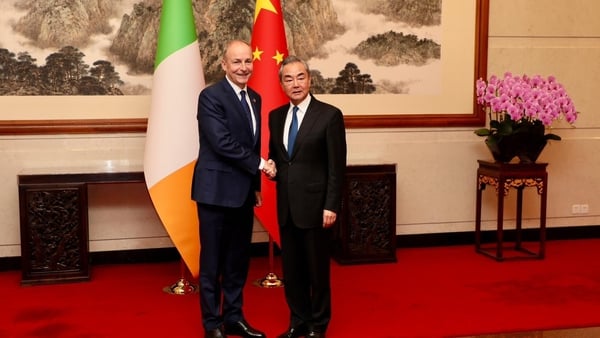

"We're very conscious that language can be misconstrued. There can be misperceptions," the Tánaiste said, following a meeting with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi.

"So, I think what I was very anxious to put across today was: Europe is not decoupling, Ireland is not decoupling. Europe and Ireland are very much up for a strong economic relationship with China."

What has also become obvious – and the Tánaiste would deny this, too – is that Ireland's approach to China is different from that of the EU.

In many ways, that is by necessity: as just one member state, Ireland is a relatively small cog in the world's largest trading bloc.

But, at a time when the EU is talking rivalries and ratcheting up trade tensions, Mr Martin told his Chinese counterpart that Ireland was anxious to "maintain and strengthen" its economic relationship with China.

To the Tánaiste, de-risking is simply about making sure that the EU can become more self-sufficient. The alternative is that it would continue to rely on Chinese supply chains if a pandemic hits, or Russian gas if Vladimir Putin decides to invade one of our neighbours.

"Every country will seek to reduce vulnerabilities," the Tánaiste said.

But, for the EU, it is explicitly about reducing what it describes as a "staggering" trade deficit. The EU imports far more from China than China does from the EU.

It is one key reason that Brussels views Beijing as a rival in both economic and geopolitical terms.

Delighted to meet VP Han Zheng at the start of my China visit.

— Micheál Martin (@MichealMartinTD) November 6, 2023

Thank you for the warm welcome, and the opportunity to strengthen Ireland's economic and cultural ties.

Discussed shared global challenges, trade, Ukraine, the Middle East, climate change, and human rights. pic.twitter.com/8HWWhdxy0y

"We must get China right. We must recognise that there is an explicit element of rivalry in our relationship," European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen told EU ambassadors on Monday.

"The Chinese Communist Party's clear goal is a systemic change of the international order, with China at its centre."

This is less of a concern for Ireland.

That's precisely why the Tánaiste subtly sought to differentiate the two positions, pointing out that, within the EU, Ireland was one of those advancing "the concept of open and free trade".

He told RTÉ News that this wasn't quite the context – that it was about making clear that Ireland is an open trading nation. But the points aren't all that different.

"Ireland's raison d'être is to have a more liberalised trading environment in the world," he said.

And he acknowledged that he was conscious that China may have a view that Europe was becoming more protectionist, or trade averse.

"We were simply stressing the point that we don't believe that to be the case," he noted.

Undoubtedly, the Tánaiste found it easy to convince his Chinese counterparts that Ireland was open to trade. The point about the EU was probably less persuasive.

In September, Ms von der Leyen made much ado about launching an investigation into China's heavily subsidised electric vehicle industry. China called it a "naked protectionist act".

The European Commission is considering doing the same about the country's wind turbine industry.

There is no doubt that there has been a strengthening of protectionist feelings against China within the bloc.

The Tánaiste declined to answer a question about Ms von der Leyen and her commission's tone, which has undoubtedly contributed to the negative Chinese perceptions of de-risking.

But he said that engagement and dialogue between the two sides was key, presumably to deaden the blow.

Mr Martin had plenty of dialogue during his visit.

At Beijing Foreign Studies University, he told future Chinese diplomats that Ireland’s interests and values only sometimes differed from China's – and that Ireland had no intention of decoupling from China.

But it was here that he expounded on two concepts at the heart of Ireland's foreign policy: the international rules-based order and multilaterialism.

In talking about what he called the consequences of a contested world, the Tánaiste had something of a captive audience.

A degree from BFSU, as it is known, serves as a passport to the upper echelons of Chinese diplomacy. Scores of the country’s ambassadors have graduated from there.

On trips abroad, the Tánaiste often points out that, as a small, outward-facing country, Ireland is reliant on other countries accepting and obeying global rules.

Multilateralism, meanwhile, is an uninspiring term for what happens when three or more countries work together on a common goal. The EU, with 27 member states, is an example of a multilateral organisation.

So too is the United Nations. And Mr Martin was just as keen to tell members about Ireland's role as a UN member state – and how it had worked with China in that capacity – as he was to talk about the EU.

"The multilateral system, with the United Nations Charter at its heart, remains our strongest protection and our most important collective global security asset," he said.

An honour to speak at Beijing Foreign Services University, 13 years after my last visit.

— Micheál Martin (@MichealMartinTD) November 8, 2023

Encouraging to see the students learning the Irish language here, and taking Irish Studies.

Your work is helping build the warm people-to-people relationships between our two countries. pic.twitter.com/8OJzAFR0Xs

The Tánaiste was prepared to ask China once again to use its influence with Russia to help bring an end to the war in Ukraine.

He was more circumspect about China's role in the Middle East conflict, but he said it had become "very clear" on his trip that China did not want any kind of regional escalation, explaining it in economic terms.

"China, it is fair to say, has no interest really in conflicts all over the world. What I mean by that is: they don't want conflict that destabilises the economy," he said.

Though it was not something he raised in any of his speeches on the visit, the Tánaiste said he broached human rights concerns with Mr Wang, his Chinese counterpart, including the plight of the Uyghur population in the Xinjiang region.

As part of an unprecedented and widely criticised crackdown on ethnic minorities, China has detained more than one million Uyghurs in internment camps and prisons in recent years.

There are around 12 million Uyghurs, who are mostly Muslim, in the region.

Read more

Inside Xinjiang: China cracks down on Uighur population

Mr Martin said he also raised China's crackdown on human rights defenders, as well as the erosion of freedoms in Hong Kong.

"I think the foreign minister was very open in inviting us to talk about these issues," he said.

But it was on Thursday, the final day of the Tánaiste's visit, that it became clear that Ireland certainly does not view China as a rival.

He officially opened the new offices of Ireland's consulate general – Enterprise Ireland, IDA Ireland, Bord Bia and Tourism Ireland all have a presence.

They very much hope Irish companies will put more, not fewer, eggs in the Chinese basket.

At China Europe International Business School in Shanghai, which was established by both the Chinese government and the EU, he told students that Ireland wanted a constructive partnership with China.

And he said that interdependence – not rivalry – would be one of the key themes emerging in the coming years.

"There's really a strong sense that, some time back, people were speculating as to whether China was going to withdraw into itself," he said, in one of his final remarks on the trip.

"I certainly don't get any sense of that this week. And it was very definitively said to us: China is open."

That message was warmly received.