In 2009, Benjamin Netanyahu delivered a passionate affirmation of the Middle East peace process at the Bar-Ilan University in Tel Aviv: "In my vision of peace, there are two free peoples living side by side in this small land, with good neighbourly relations and mutual respect, each with its flag, anthem and government, with neither one threatening its neighbour's security and existence."

Fast forward to 28 October this year and Israel’s prime minister was invoking Hebrew and Christian scripture to justify his country’s merciless assault on Gaza.

"With shared forces, with deep faith in the justice of our cause and in the eternity of Israel, we will realise the prophecy of Isaiah 60:18 - 'Violence shall no more be heard in your land, desolation nor destruction within your borders; but you shall call your walls Salvation, and your gates Praise'."

"This is a time for war," he told Israelis in a televised address.

The ruins of Gaza certainly feel apocalyptic, if not biblical. In South Korea, Taoiseach Leo Varadkar said Israel's actions were "approaching revenge."

The death toll in Gaza is nearing 10,000 with thousands more injured.

UN agencies say 1.5 million people, more than half the population, are displaced.

One third of the enclave’s 35 hospitals are no longer functioning.

Only 374 aid trucks have entered Gaza since the 7 October Hamas attacks, compared to 400 per day beforehand. Children are falling sick through drinking dirty water.

The dystopian landscape reflects a desperate lack of hope that this calamity can end soon.

Israel is pursuing what it regards as its survival as a state, while in the Arab world - and in much of the West - the charge of genocide is freely levelled.

The conflict is bleeding into the global culture war. Unquestioning allegiance to one narrative or the other, fuelled through social media and rippling through domestic politics, has created a furious binary debate, driving people into street and campus violence.

Yet, calls for a revival of a Middle East peace process, based on the two-state solution, have never been more passionately - or desperately - proclaimed.

"When this crisis is over," President Joe Biden said last week, "there has to be a vision of what comes next, and in our view it has to be a two-state solution."

One consensus appears to be holding - within Israel and internationally: the author of that 2009 speech and its Biblical follow up last weekend cannot be part of a "day after" peace process.

Whatever about his reputation globally, Benjamin Netanyahu has faced a storm of criticism both from within his own centre-right Likud camp, for the intelligence failures that led to the Hamas incursion on 7 October and among Israeli liberals for his strategy, begun even as he made that euphoric speech in Tel Aviv, to cynically undermine the Palestinian Authority in order to destroy that two-state solution.

'Israeli interests better served by Palestinian disunity'

It is widely accepted in Israel that when the Israel Defense Force withdrew from Gaza in 2005 and Hamas took control of the enclave in 2007, Mr Netanyahu tacitly accommodated the organisation - facilitating the flow of a reported $1 billion of Qatari money, some of it in suitcases, to Hamas's coffers - in order to undermine the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank and to show to the United States that he had no reliable Palestinian partner.

The Jerusalem Post reported Mr Netanyahu admitting as much in private comments to his Likud Party in March 2019.

The dramatic expansion of Jewish settlements in the West Bank all but completed the process by which a continuous Palestinian state was impossible.

"[Netanyahu] espoused the ill-fated notion that Hamas's rule in Gaza was fundamentally good for Israel," wrote the former director of the Israeli internal security service Ami Ayalon and Gilead Sher, former chief of staff to Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak, in Foreign Affairs.

"Israeli interests were better served by Palestinian disunity - with Gaza split from the West Bank, where the more moderate PA holds sway - than by political unity among Palestinians,".

This strategy appeared to be working. The relationship between Israel and the Iran-backed Hamas erupted into war every couple of years, but nothing resembling a full-scale escalation.

Israel strengthened its border defences and ramped up hi-tech surveillance and human intel within Gaza; Hamas dug a maze of tunnels and armed itself with ever more lethal and longer range rockets.

A further strategy was to normalise relations with the Arab world.

Mr Netanyahu signed the Abraham Accords with Morocco, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates.

They recognised Israel's right to exist in return for diplomatic relations and market access. The Biden administration hoped it could keep the Middle East further at arms length by negotiating the big prize: normalising relations between Israel and Saudi Arabia.

The US turned a blind eye to Mr Netanyahu’s toleration of Hamas.

"That assumption was widely shared by Western officials: toppling Hamas, they feared, would result in a power vacuum that Israel would have to fill by directly ruling Gaza - a prospect that Israel has long shunned," says Assaf Orion, formerly the head of strategic planning on the Israel Defense Forces General Staff.

Extreme right nationalist parties

Up until 7 October, Mr Netanyahu appeared to regard Hamas as a manageable asset.

The Palestinian Authority under the aging Mahmoud Abbas was ineffectual. The rapid expansion of Jewish settlements was delivering the creeping annexation of the West Bank that promised to kill off the two-state solution.

This was done in plain sight. In the 2022 legislative elections, Mr Netanyahu invited two extreme right religious nationalist parties - the Religious Zionist Party and the Jewish Home Party - into a governing coalition, giving the leader of the former, Bezalel Smotrich, special powers within the defence and finance ministries.

In 2017, as a member of the Knesset, Mr Smotrich had called for the rapid expansion of settlements and the annexation of large swathes of the West Bank.

In a long essay, he wrote that Palestinians swallowed up into this expanded Israeli entity would either be second class citizens, or, if they failed to demonstrate their loyalty to Israel as a Jewish state, would be "encouraged" to emigrate to other Arab countries.

Describing that plan as close to genocide under Article II of the 1948 Genocide Convention, the former US ambassador to Israel, Martin Indyk, and president of the International Peace Institute Zeid Ra’ad Al-Hussein, described Mr Smotrich’s blueprint as "explicitly designed to eliminate Palestinian identity itself by crushing any hope for a Palestinian state and forcing the Palestinians to live under Israeli rule with differentiated rights."

Mr Smotrich’s essay may not have been simply the freelance thinking of an extremist politician in opposition.

This week the Times of Israel reported that Israel's Intelligence Ministry had drawn up a paper proposing the forced removal of 2.3 million Palestinians from Gaza into tented cities in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula as one possible outcome of the current war.

The government played down the ideas as being part of a "concept paper", but they were quickly condemned by the Palestinian Authority as echoing the uprooting of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

Two-state solution

Given the grim history of the Middle East since the days of the Oslo Peace accords 30 years ago in September, it is not surprising that popular support among both sides for the two-state solution is in the doldrums, while disenchantment with the peace process, and deepening enmity, are widespread.

An Arab Barometer survey in January, in conjunction with the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, found that only 33% of Palestinians and 34% of Israeli Jews supported the two-state solution, with 66% and 53% opposed respectively.

This compares to 43% of Palestinians and 42% of Israeli Jews two years ago.

While the two-state solution is more palatable for both sides than any other peaceful arrangement, Palestinians and Israeli Jews have increasingly polarised views of each other’s rights.

According to the survey, 84% of both Palestinians and Israeli Jews regard themselves as an exclusive victim, while 90% of Palestinians and 63% of Israeli Jews believe their suffering grants them a moral right to do anything they deem necessary for survival.

Ninety-three percent of both groups see themselves as rightful owners of the land between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan river.

While one third of Israeli Jews are willing to accept some ownership rights for Palestinians, only 7% of the latter feel the same about Israeli Jews.

Peace process

Support for a peace process as the next step has declined on both sides. Some 40%of Palestinians, up from 37% two years ago, would prefer "armed struggle" against the Israeli occupation, while 26% of Israeli Jews want "a definitive war" with the Palestinians to resolve the conflict.

All of this was before the events of 7 October and Israel’s military response, but already worsening clashes in the West Bank between Palestinians and extremist Jewish settlers since 2022 had hardened attitudes.

Ironically, Palestinians living in Gaza are historically more likely to have supported the two-state solution.

Surveys have also shown that with every heavy-handed response or when Israel tightens the economic blockade, support for Hamas increases (although support fell to its lowest level after the 2014 Israel-Hamas war).

Right before the current bloodletting, "rather than supporting Hamas, the vast majority of Gazans have been frustrated with the armed group’s ineffective governance as they endure extreme economic hardship," say Amaney A Jamal and Michael Robbins of Arab Barometer.

"Most Gazans do not align themselves with Hamas's ideology, either. Unlike Hamas, whose goal is to destroy the Israeli state, the majority of survey respondents favoured a two-state solution with an independent Palestine and Israel existing side by side."

Yet, with all sides drifting to the extremes, even before 7 October, reviving the two-state peace process seems like a Herculean struggle.

But there are small glimmers of hope.

All sides seem sure that the status quo is no longer tenable. Israelis are almost certain to demand an election after the calamity of 7 October and there are likely to be penetrating inquiries into the political and security failures going back years.

The United States and EU both accept they must forcibly revive the peace process.

While Europe admits that Washington takes the lead, diplomats have said the last statement of substance by EU foreign ministers on the Middle East Peace Process (MEPP) was in Luxembourg in December 2016.

Looked at through the paradigm of the Arab Peace Initiative, launched in 2002, a two-state solution would involve a return to the pre-1967 borders (i.e., Israel pulling out of the West Bank, Gaza, the Golan Heights and Lebanon) and land swaps (the allocation of arable land from within Israel proper to Palestinians as compensation for the annexation of West Bank land by Jewish settlements).

There would be a "just settlement" of the return-of-refugees issue, and a Palestinian state with its capital in east Jerusalem. Arab states would then recognise Israel and sign peace treaties.

While international reaction to the Arab plan was broadly positive, US and Israeli reaction ranged from supportive, to neutral, to negative.

Ultimately, Israel rejected the plan because there would be no guarantee that radical groups, bent on Israel's destruction, would not use the withdrawals to embed terrorist bases on evacuated territory.

While the plan was re-endorsed by Arab states in 2013, Likud's inexorable preference to kill off the two-state solution meant the Arab Peace Initiative has remained in deep freeze.

Two-state solution in new light

John Lyndon, the Paris-based Irish director of the Alliance for Middle East Peace (ALLMEP), believes that ultimately the Initiative came unstuck over territory and what bits of land got swapped where, and not over the final status of refugees or Jerusalem.

Paradoxically, however, Mr Lyndon believes the 7 October terror attacks may allow people to look at the two-state plan in a new light.

He says that on the eve of the attacks, some 26 Israeli Defense Force battalions were protecting isolated Jewish settlements in the West Bank, thus leaving Israeli communities near Gaza horrifically exposed to the massacres which transpired.

The cost of protecting so many isolated Jewish settlements in the West Bank will therefore become a problem for Israel.

"Once you get beyond a ceasefire," says Mr Lyndon, "whether it's by a commission of inquiry, or even just press reporting, Israeli citizens will see this, that actually the settlements very clearly create a security burden for Israel.

"If you factor in the north and Hezbollah, it's simply impossible for Israel to defend far-lying settlements, and to defend the Gaza border and defend against Hezbollah as well. This is why the two-state solution may suddenly have a little bit more attraction to it."

As an example, a settlement of 800 Jewish citizens in Hebron requires 2,000 Israeli troops to protect them, surrounded as they are by a population of 35,000 Palestinians.

"These questions will be posed by the Israeli electorate in the election that hopefully comes after this war," says Mr Lyndon.

A resurrection of the peace process does not just depend on a cost-benefit analysis by Israel.

It is impossible to gauge what state Hamas will be in after the war, and what their support levels will be.

Axis of Resistance

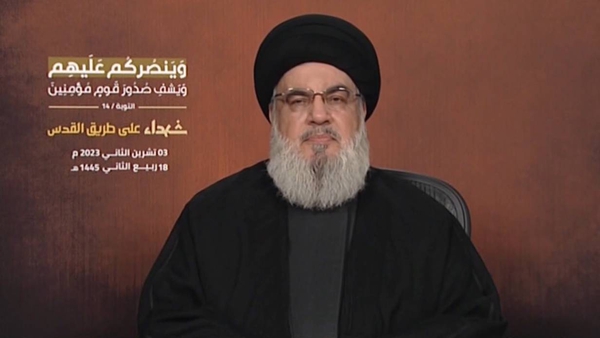

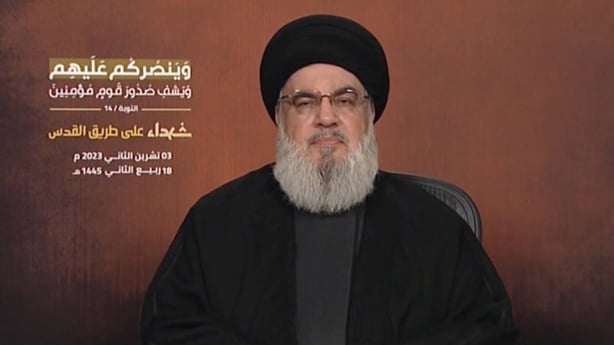

Where the Palestinian Authority and so-called Axis of Resistance fit in - Hamas, Hezbollah, Houthi rebels in Yemen, Iranian militia in Iraq, and Iran itself - will be a complicated issue.

The Palestinian Authority cannot be seen to be taking over Gaza on the back of Israeli tanks.

Iran relies on perpetual instability in the Middle East around the Arab-Israeli conflict, hence its - and Hamas's - real concern that Israel and Saudi Arabia were on the brink of normalising relations.

An ongoing crisis in the region that draws in the US and Europe also suits Russia and China.

On 1 November, Ghazi Hamad, a senior Hamas figure, told Lebanese television that attacks like 7 October would continue until Israel was "annihilated", so Israel will not countenance any peace process which involves Hamas.

The international community will have to figure out who runs Gaza once the war is over, and who will pay to rebuild it.

Mahmoud Abbas is 87 and does not command the majority support of Palestinians in the West Bank, and he has not groomed any natural successor.

A survey carried out by Arab Barometer just before the 7 October attacks found that if presidential elections were held in Gaza, Mr Abbas would win just 12%, while Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh would get 24% and the jailed Fatah member Marwan Barghouti would win with 32%.

According to Mr Lyndon of ALLMEP, Palestinian disunity has plagued the community for decades and is the source of worry for voters, more so than the occupation.

Pulling a two-state solution from the fires of Gaza would require, therefore, a new non-Hamas generation of Palestinian leaders, a post-Netanyahu political landscape in Israel, and an agreement among Gulf Arab states, as well as Egypt and Jordan - each of whom is reputed to favour their own Palestinian clients to outflank their rivals - to weigh in with diplomatic and financial support.

"All of that [rivalry] needs to end, and we need to be focused on an outcome of two states and what needs to be done in order to engineer that," says Mr Lyndon.

Others are less sure.

"Preserving the two-state option for the future was already a challenge, given the PA's abysmal situation and Israel’s increasingly polarized politics in the years and months before 7 October," says Assaf Orion, the former head of strategic planning on the Israel Defense Forces General Staff.

"Since then, it has become even more far-fetched."

The mindset within much of the Israeli population, and the military leadership, is that Israel was created in order to guarantee a safe home for Jews following the Holocaust and centuries of persecution, and that the 7 October massacre of 1,400 Israelis has meant that guarantee can no longer be upheld with status quo options.

There is talk of a long war to uproot and destroy Hamas, essentially a security solution to a security problem, whatever the cost to the civilian population in Gaza.

Yet, Hamas remains an ideology of resistance that may re-awaken in another guise, unless Palestinians are given an alternative future to believe in.

For now, however appalling the odds, the west and the Arab world believe the two-state solution remains the least worst option.