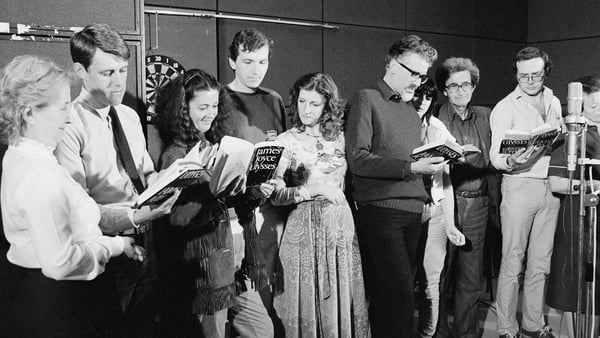

Below, writer and poet Aidan Matthews introduces Bodies In Bloom, an illuminating essay on James Joyce and Ulysses, presented ahead of the RTÉ One Extra presentation of the epic 1982 dramatisation of Joyce's masterpiece, to be broadcast in full this Bloomsday - find out more here.

Bloomsday and Corpus Christi tend to occur within each other's octave, as they did in 1904, unless Easter is exceptionally late.

As a veteran of both, I find this closeness of conjunction very pleasing, because the two festal events - one civic, one ecclesial - celebrate the same thing: the sacredness of the ordinary world - human, mineral, and vegetable - as it ripens toward the summer solstice. The bread of life is always the bread of bodies.

Both celebrations have their detractors: the medieval church repeatedly condemned the Corpus Christi procession as pagan (ditto progressive theologians today), and Puritans in the cultural commentariat, who are always prurient, insist that Poldy Bloom would be on the sex-offenders' list in 2020, which is probably the case. Feminists too entertain significant scruples about Joyce's earth-mother approach to the female sex.

Our current preference for the sensuous and the sensual is not, in fact (or fiction), a final victory. it is only a truce in an eternal conflict between delight and disgust, between the horizontal and the vertical - or, to use the basic Joycean binary, between Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom.

Bodies In Bloom

Before I heard of Bloomsday, the Feast of Corpus Christi was the major public event in the calendar for June. The Whit weekend at the start of the month had long since lost any liturgical authority and become instead a breakaway Bank holiday; St. John the Baptist's feast-day was marked in remote parts of the country by bonfires on the hillsides, but the only flames he started in the city were a couple of candles in his own patronal churches; and the summer solstice was ignored by everyone, even the Meteorological service. It had taken fifteen hundred years for the Church finally to smash the pre-Christian tradition of song-and-dance at Midsummer, and they had just about succeeded as Joyce wrote his first A.M.D.G. on a school essay.

When I was writing mine, about a lifetime later, Corpus Christi was unchanged. In its essentials and in its etcetera, it remained the same processional ceremony it had been from the beginning, a Counter-Reformation recreation of a medieval cult which earlier church authorities had attempted to embargo, an event dedicated to the greater glory of the incarnate God in the Eucharistic species. As such, it may have been a theological impropriety, and it was almost certainly a provocation to the Reform minorities whose sacramental thinking was less florid; but, for at least one middle-class schoolboy in an Edwardian quarter of Dublin, it was by far and away the most beautiful rite of his boyhood and the most enabling memory of his largely dismembered origins.

The holy day of obligation itself fell, and falls, on a Thursday. More sleep, less school, and hymns that Thomas Aquinas would have fled from (devotional work was the only safe house for carnal expression in the days of thin lips and long faces, when Dublin was more Genevan than Geneva) made that moveable feast a case of iron rations; but the Sunday following was a banquet. Where the bread and wine ended and the bread and circuses began, is a matter of drawing lines; and I’m more interested in circles. At any rate, the line which left the church grounds after solemn high Mass was never linear: girls in their Communion dresses scattered rose-petals at the foot of the monstrance, a silver stellar mass, shaped like a supernova, with the huge white host at the heart of it, frosted and glassy, a compass-face; and the vested parish priest held the sacrament up and up and up higher until it touched the pleats of the canopy which the stewards carried on poles to protect the Bread of Life from the dust and insects of Donnybrook.

I look behind me. In my new glasses, my tortoise-shell wings, I can see more clearly than at any other time in my nine years of age, my three thousand days in this blur of a world. I can see my parents and my brothers and my sisters and my uncles and my aunts, two or three faces divided among the thirty members of a family: the stupidly oblong look is common to all, the jowls, the jawbones, the warmly auburn eyes. Only the details differ – here a mantilla, there a hearing aid; bouffants, bald patches.

"Joyce," my father said, "is not really suitable." So Ulysses disappeared into the drawer of his bedside table, where he kept liver salts and a photograph of his father at the mouth of a tunnel. Although he gave me Dubliners in an old Penguin paperback, I decided he was a censor and a commissar. If a child does not have a patriarch, he will invent one.

Over the bridge at the Dodder river, where the heron stood among the hoods of broken prams, and along the main street of Donnybrook village, walked the few hundred followers of the God of Hosts. Altarboys with thuribles, acolytes with blown-out candles, pregnant women and those partly responsible, two White Russians and a ball-turret gunner in a Lancaster who’d watched Dresden burn with, he said, the blue flames of a plum pudding. Policemen outside the Huguenot grave-yard took off their hats and kneeled at the bus-stop as the procession passed. Bunting in the Papal colours hung from the window-sills, and streamers were shoe-laced on the wrought-iron gates of the Magdalene convent. And why not? For everything in this lovely field of vision was blessed: the dog-s**t, the horse-troughs, the automatic bubble-gum dispensers outside Woods’s newsagent’s, even the shoe-shop owned by Presbyterians, were sacred in a world where the Word had been made flesh and dwelled among us.

The author of the longest short story in the language is writing about a journey and not a destination.

"Joyce," said my teacher, "is in the Society of Jesus." Thirty of us waited in our desks as the young scholastic wiped the blackboard clean with the dark wing of his soutane. The smells of egg and banana rose around us, and the leather of wet winter shoes drying on the classroom radiators.

"By that," he told us, "I don’t simply mean that Joyce is in Paradise – which, by the way, is a poor place for a writer to find himself, since the term implies that Heaven is beyond the power of utterance. I mean as well that Joyce is a Jesuit. You cannot read him anymore than you can read the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius Loyola. You must instead do both."

Why on earth am I talking about the Corpus Christi procession in an essay on James Joyce? To be sure, the neurasthenic adolescent who lived, moved, and had his being at the close of the nineteenth century was as much a child of the Council of Trent as any boy born into a Roman Catholic household up to the closing sessions of the second Vatican council in the middle nineteen sixties. But a sum of shared circumstances – the Latin Mass, say, or a continuity of curriculum at different Jesuit colleges – produces its own deficit: perspective is the gift of distance. The teenager who trekked between Mariolatry and masturbation in his final years at school and his first years at university offered a precedent and a paradigm for one whole generation of which I can say something, yet it well may be the case that only an outside reader from another culture is able to spot the fake nature of that conflict, the binary back-and-forth from sin to sacrament which Joyce notates ironically in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

This is not to deride the portrait of the young man who became a great artist. Joyce was enough of a Victorian to savour the image of martyric sexuality which he elaborated in exile, and enough of a snob to delight in the Jesuit connection. Baroque ebullience transformed his wet-dreams into vales of tears, and the high-caste connotations of style and setting point to a petit-bourgeois terror of detection, to a man who looks at his nails before knocking. All of this makes him a perfect guide to the ground of our culture, a psycho-sexual arrow. We understand the lack of social confidence, the Crown-colonial motility of place, prestige, and profit; we understand too the inner onus, conscience and conscientiousness, our sense that every instant of our lives is the venue of moral scrutiny. We understand these things, and we stand over them as well.

In a word, Joyce is incarnational.

We are talking, then, about the body and the body politic. The literal and the literary world of Joyce’s early manhood abounded in texts which treated the two themes, yet the first had been vitiated by a sort of operatic nastiness, and the second was all too often tendentious, a demonstration of the city not as placenta but as afterbirth. Joyce was to join the two parties in a dialectical act of possibility, wedlock out of deadlock. First, however, he had to learn his negotiating skills. His culture didn’t immediately privilege him. As much as anyone else, he was trained as a necrophile of the Cross and spared the rigours of pathology only by his apprenticeship to Church Latin. It was his first taste of oral sex, of orality, the chapel of the mouth, the decent sensuality of language as strangeness: phrase and cadence, the verb at the root of words. Yet to become, as he did, a humanist of the Incarnation, it was necessary to lay aside the narcotic diction of the Fathers, the implacable maleness of Latin, and take to heart instead the alterity of everyday speech.

Because he was a Thomist, albeit a doubting one, Joyce was an Aristotelian; and Dublin is, par excellence, an Aristotelian city. This doesn’t, for a moment, mean, as Joyce insisted it did, that you can reconstruct the place from a reading of Ulysses, though the opposite may be so. The author of the longest short story in the language is writing about a journey and not a destination. He is no Bonapartist visionary creating a capital: his Champs Elysees is strewn with very soggy cow-pats and quite exquisite thistles. The Dublin of all his works and days is as close to the Augustinian City of God as it is to the seminarians who walk in threes (numquam duo) through the streets of the inner city. More accurately, the City of God and the City of Man are one and the same. Mysticism and materiality long for one another, and belong together – as the best mystics and materialists have always known. Marx would have loved this book – the unified, though never unitary, work we call his four novels – and Heidegger should have. It is the best social history of the period and a hermetic journal worthy of Meister Eckhart (if, of course, the latter had been a Jesuit and not a Dominican).

In a word, Joyce is incarnational. He disconcerts – if, indeed, he doesn’t all together destroy – the established ecclesiastical decorum of his day (and ours) by reaching back beyond Vatican latinity and patristic Greek to the ordinary everyday Aramaic of human life, the deep-down demotic of the world we people. Here, he tells us, is the good news, the gospel truth, the New Jerusalem: it is called Nazareth – or, in another dispensation, Ithaca. It is a place where we make the most terrible assumption of all, and that is the assumption of flesh; a place where we live not in the present, as the Christian charismatic asserts, but in time, in the stress and distress of the subjunctive, in the eschatological drama of nine fifteen in the morning or twenty past three in the afternoon. There, in the space between self and other, between story and history, lie all our narratives.

"Inter faeces et urinam nascimur," Saint Augustine says, but the grief and grievance of the Bishop of Hippo is worlds away from his Irish namesake. To be born among shit and piss doesn’t condemn us to cloacal histrionics (Jim the latrine is a common reprimand); rather, it commits us to our green and venial nature, to the solid adequacy of our limitations, the purity of our imperfection. The body and the body politic reek of their second-hand status. Both of them speak the language of damage, of migraine, of imagination; and both thereby sabotage totalitarian models, the sunstroke of lunatics. There are other masters of modernism (some of them Irish) for whom the journey from the mouth to the anus, whether social or sexual, was at times a day-trip, at times a night-crossing, the distance between income and outgoings, between the kiss and the crisis. For Joyce, in the odyssey of his own voyage from Jansenist disgust to somatic gusto, a sum of crossroads came to map the two encampments, common flesh and the human community, comings and homecomings.

Yeats did the same thing differently, as indeed did Beckett. Joyce, being neither as Monsignorial as the former nor as ascetical as the latter, found a middle way, a modus operandi between prince bishop and Puritan divine. He became a parish priest, the rabbi of Bedlam, a site that was half-ruin and half-scaffolding, Pompeii with tram-lines: Babel in a bad mood, Pentecost in a good one. Many Adams walked this way in their span of seventy years or less, a walk from mud to dust along the side-streets where fly-posters advertised helium. It was Joyce’s way. He may not have carried a canopy over the monstrance in his mature years, but the Christ of the body would have respected the Feast of Corpus Christi for its mutuality of intention in consecrating the wall-fallen districts of the diocese.

A holiday and a holy day, Bloomsday has a habit of making history: the 1953 uprising in East Berlin, the bungled Watergate burglary, the Soweto revolt in South Africa.

To claim him as a democrat is not, of course, to disclaim his defence of the private person. Joyce in his blindness had the sonar of bats when it came to the labyrinthine, idiorrhythmic inner life of the individual, whether the social man in his solitude or the solitary man in his society. So Portrait opens with the most ancestral of all introits – "Once upon a time" – and ends with a diary entry in apostrophes to oneself. In the same way, the Latin introit of the opening of Ulysses is prefaced by the portly binocular prose of mass readership fiction, and ends, like Dubliners, in a down-drift, a snow-storm, an incandescence, a blizzard behind the eyes. Yet the private life does not end in a personal existence, in the unholy trinity of all those pronouns, I, me, and myself. Instead, there’s a summoning, a summing up, a versatile, impersonal richness, until the whole people, the glittering polity, is seen as many and unanimous, going down, in Finnegans Wake, into the uterine curvature of space-time, into the amniotic realm, the waters of life and of Lethe, like the pilgrims in Benares bathing in the Ganges. This is, it seems to me, the mystical vision; and it was Joyce – a sponger, a show-off, a cadger, a grouse, a monomaniac, a conspiracy theorist – who had it, held it, held onto it, as he walked among the sparrows picking grass-blades from the horse-droppings along the Appian Way at the foot of Lower Lesson Street.

Footloose or footsore, Joyce was always that same walker - and to be a walker is always to move at a slightly more startled, vigilant pace than your average boulevardier. When a capital city is also a garrison town, the steady pace of a promenade may yield at times to jittery diagonals; and, in any case, the incentive of empty pockets keeps a man stepping smartly, if only to outstrip the breeze. Yet it’s that very pennywise fretfulness which saves the Joycean city from facile optimism, from Periclean adjectivity. The brave new world is also big and bad, here and elsewhere, too; for Joyce, our premier emigrant, a peregrinus pro Christo in the Celtic Christian mould, was himself as travelled as Ulysses, and knew the secret of every dispersion, Irish or Jewish: that the first city was founded by a nomad in the land of Nod, and remains the creation of Cain.

Entrances and exits, the walk-on parts of minor personages, the pedestrian basis of the books he wrote, his Odysseys in a world of Iliads, his best foot forward: here is a man who stretches all our legs (and often pulls them). And here too is a walkabout that continues. On Bloomsday each year, in a mimesis, a Mardi Gras, the youngsters and the young at heart gather together and go out into the streets of the city, a city set on a hill (no longer visible) beside a river (no longer translucent), and they wander. To wander is to wonder, or, at any rate, to be wondered at, especially if the wanderer is wearing the britches and bowlers of an earlier era or the dove-tailed skirts of a slattern from the turn of the century. For this is the Feast of Leopold Bloom and his melonsmellonous Molly, which feast-day is itself a commemoration and celebration of the day that a young man and a young woman first walked out together into the light and shade of the funeral games of Europe. A holiday and a holy day, Bloomsday has a habit of making history: the 1953 uprising in East Berlin, the bungled Watergate burglary, the Soweto revolt in South Africa. But it remains, in essence, a carnival of the ordinary, a salute to the hairs in the soap and the mercury in our teeth. It affirms a baffled, vulnerable, fallible man against ideological hygiene and the blandishments of dogma. It invites street parties, song and dance, a procession, a parade, bread and wine, bread and circuses.

It has become a fixture, this praise of flux. It has become an event. It may even end up being solemnized. When we do things routinely and regularly in this country, we say we do them religiously. Joyce would enjoy that.