To chime with Bloomsday, RTÉ Arts and Culture commissioned a series of short essays on the idea of walking out, something which is at the heart of James Joyce's Ulysses.

The Avenue is the contribution of writer Ian Maleney - read it below.

'..I am picturing the road she is walking on, a road I could draw from memory even now, a road that I walked more than once at some ungodly hour of the morning home from a friend's house in town, a few drinks in me making me sentimental and poetic as the sun came up…’

Every morning my mother walks, navigating the narrow roads and blind corners, from our house to the outskirts of the nearest town, before turning around and walking back the way she came, until she arrives home a little lighter and much more ready to face the day ahead – she calls these daily perambulations, which take an hour and a half at least, her 'sanity walks' because they get her out of her head and into her feet, breathing a little harder, the blood flowing, and she has always needed that: she is an extrovert, always doing things and going places, and she'd chat away to anybody (as she said to me recently, ‘I actually like people’, a statement with which I could only agree and note my own difference of opinion regarding the general population), so being cooped up at home all day is no good at all for her state of mind; she has painted everything in the house as far as I can tell, all the rooms and the hall and much of the furniture, her photo updates typically arriving over WhatsApp along with news of my grandmother, who is not well, and news of the bog, where the turf is done and home, and news of her own – my mother's that is – ongoing root canal debacle, the details of which I won't go into here because even in these gossip-starved times no one wants to hear about a stranger's teeth, but sometimes she calls me too, to tell me she has no news, and when she calls me, she is often on one of her sanity walks, my brothers and I having bought her a pair of AirPods for her most recent birthday so she can now walk and talk in some comfort, and given her usual strategy of calling me on the handsfree as she drives home is no longer viable because she has nowhere to drive to and therefore nowhere to come home from, these walks in the morning or in the evening are good opportunities to call me up and update me on how many miles she's done this week, or to announce that she is raising money for some charitable cause (by walking), or that a Zoom meeting with a client or a colleague had gone well, or that something in the news was maddening – and while she is telling me all this, and I am on the other end of the phone (with no news at all, saying 'Yeah', 'Yeah', 'Well, that's good'), I am picturing the road she is walking on, a road I could draw from memory even now, a road that I walked more than once at some ungodly hour of the morning home from a friend's house in town, a few drinks in me making me sentimental and poetic as the sun came up, a road I cycled down in the dark with no lights, a road I walked down with L when we would get off the bus together after school, the road – I remember now – where L's baby sister was once briefly abducted before escaping from the back of her captor's white van, and I remember I was in Malahide that day, walking the marina, when I saw the report on the news and I said to my walking companion, I know that road, my god, I know that house – it's not something you expect to see on the Six One News when you're wolfing down a cod and chips in some bougie watering hole by the sea, and I must have called my mother to find out what was going on, to get the details, because I knew she'd be talking to everybody then, all her friends and all the neighbours because, now that I think of it, that was probably the most dramatic and terrifying moment anyone could remember on that road, that road which all the mothers walk endlessly up and down in their immaculate tracksuits and reflective windbreakers, trading gossip and passing comment, and I can only imagine how it is now: three months into the greatest pause in the history of our lives, ninety days of emptiness, inaction, solo sanity walks and fleeting, half-shouted stop-and-chats across the width of the road; everyone desperate for news, hungry for drama and life and excitement, because there's only so much you can get from walking the same old paths in mind and conversation before you need something fresh to tell people when you call them up or bump into them on the road, but maybe that – the abduction, I mean – is something I can ask her about – my mother that is – next time she calls.

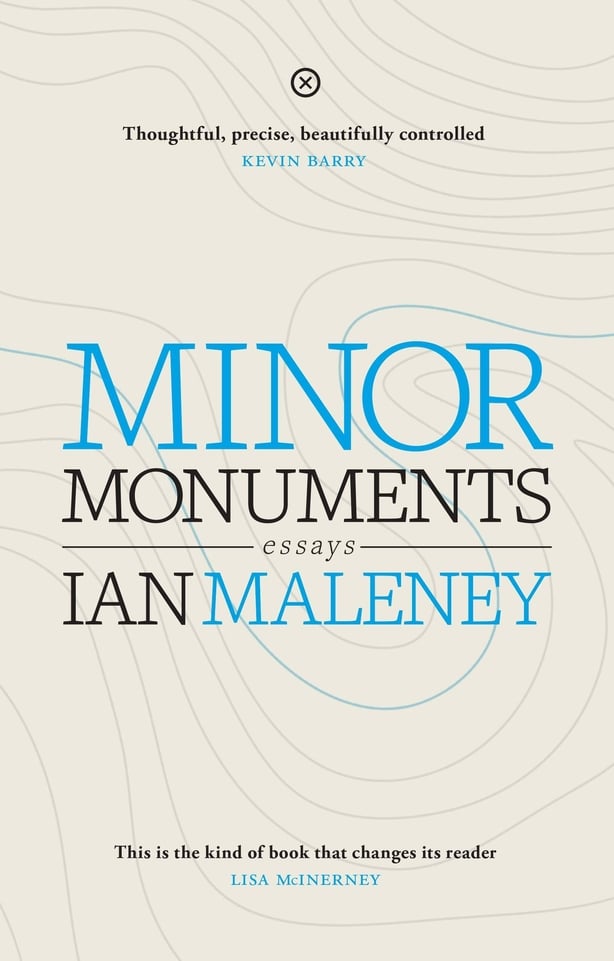

Ian Maleney is the author of the book of essays Minor Monuments, published by Tramp Press.

Compiled by Clíodhna Ní Anluain