To chime with Bloomsday, RTÉ Arts and Culture has commissioned a series of short essays around walking out, which is at the heart of James Joyce's Ulysses.

Below, read the contribution by novelist Joseph O'Connor, and watch an extract above.

'…trudging around the seafront on rain-soaked Sunday afternoons, sheltering in battered bandstands and bus shelters. Miles in the sunshine. Miles in the cold. We would talk and kiss and talk a bit more as we walked the thousand miles of teen-hood…’

When I was seventeen, I fell in love for the first time. I remember us going to only one gig, Moving Hearts in the National Stadium on St Patrick’s night, 1981, and one play at the Gate Theatre, The Elephant Man.

Mostly, when together, we walked.

Up and down Dun Laoghaire pier on the sultry nights of youth, through dusks and red sunsets and the coconut aroma of gorse along The Metals, or trudging around the seafront on rain-soaked Sunday afternoons, sheltering in battered bandstands and bus shelters. Miles in the sunshine. Miles in the cold. We would talk and kiss and talk a bit more as we walked the thousand miles of teen-hood. We were broke. Shank’s Mare was all we could afford. When you’re young and in love, that’s grand.

When some years later I read Joyce, I was struck by the fact that his masterpiece Ulysses is at heart a gorgeous intersection of walks, indeed that it commemorates the date of two young lovers’ first walk, 16th June, 1904, when Joyce and Nora Barnacle went strolling. It was also likely the date of their first sexual intimacy, beautifully and frankly imagined by the writer Nuala O’Connor in her fine novel Nora. Those shocked or pretending to be shocked by Normal People would find much to disconcert them in the notes exchanged by young sweethearts Jim and Nora, perhaps much to recognize, too.

At the time of Joyce and Nora, courtship was perhaps more codified than it is now. ‘Walking out with’ was the stage after ‘being introduced’ and before ‘keeping company’. I can remember my own Francis Street aunts using both phrases in my childhood, and somehow you knew what they meant.

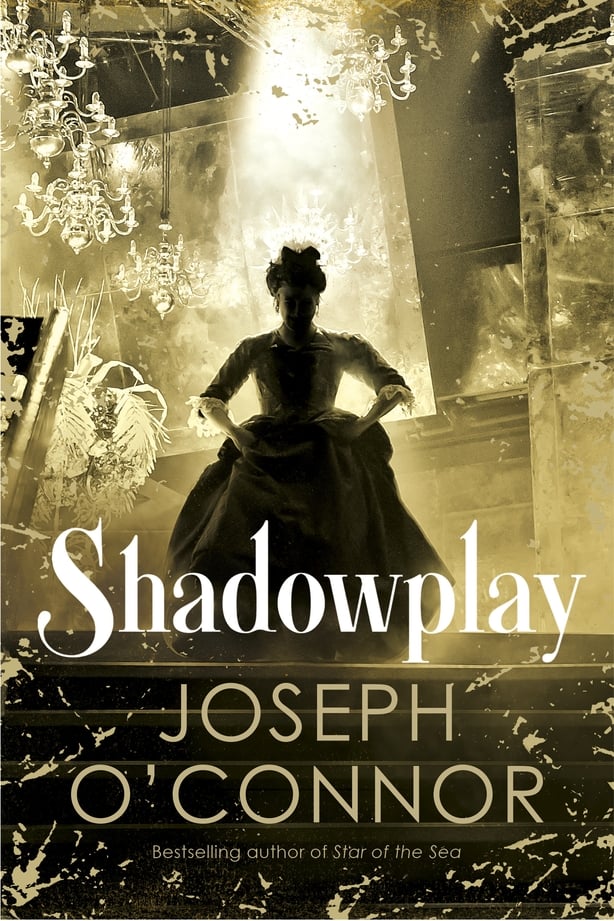

Some years ago, researching my novel Shadowplay, I happened across a Victorian book of etiquette: ‘No gentleman will ask a young lady to go out walking with him alone, unless and until they have become well acquainted by family members or friends. Nor would a lady go.’ But Nora and Jim went, walking boldly into love and the shimmer of literary history.

Those shocked or pretending to be shocked by Normal People would find much to disconcert them in the notes exchanged by young sweethearts Jim and Nora, perhaps much to recognize, too.

Walking is all over the pages of Irish literature. Eavan Boland’s beautiful collection A Poet’s Dublin is the work of a walker, a watcher. Paula Meehan, too, has walked every cobble of the city her poetry brings to such vivid life. Think of JM Synge and Molly Allgood’s strolls around the backwoods and cart-tracks of the Dublin-Wicklow borderlands, how he signed his love letters to her ‘Your Old Tramp’. In John McGahern’s gorgeous story, A Gold Watch, a young countryman who works in Dublin returns home in the summertime to help with the hay, and walks ‘the three miles from the station’ through a landscape of bliss, to find his old work clothes, laundered, hanging on a chair in the sunshine.

From Brendan Behan’s ramble around Europe with the late Anthony Cronin, described with such magnificent humour in Cronin’s Dead as Doornails, to the urgent trek of Orpen in Sarah Davis Goff’s Last Ones Left Alive, to Colm Toibin’s masterful travelogue Bad Blood: A Walk Along The Irish Border, the walk is something Irish writers have long considered subtle and central, capable of revealing much. Nor are they alone. The lexicon of fabulous American Country and Western song titles would be a poorer thing without that classic of the broken-hearted genre, I Bought the Boots That Just Walked Out On Me.

My favourite two sentences in Ulysses, perhaps in all of Joyce’s work, see walking as a metaphor for reading and storytelling, in a way for the act of empathy, too. In these deft, beautiful words, he reminds us that to walk into the heart of another is really a sort of homecoming. ‘Every life is in many days, day after day. We walk through ourselves, meeting robbers, ghosts, giants, old men, young men, wives, widows, brothers-in-love, but always meeting ourselves.’

Every day that I’m at home in Dublin, my wife and I walk. Unless the rain is actually horizontal, we’re out there. Walking together has become the best sort of ritual, the kind you don’t have to dress up for; something that simply gets done. To walk is to read the world, to see where you’re going or a respite from having to bother to think about that. Shank’s mare. The sound of footsteps on street or pebbled seashore. The fleeting happiness you hardly even notice.

Joseph O’Connor’s novel Shadowplay is published in paperback by Vintage. It won the An Post/Eason Irish Novel Of The Year Award, and was shortlisted for the Costa Novel Award.

Compiled by Clíodhna Ní Anluain