We present an extract from Death in Irish Prehistory, the new book by Gabriel Cooney, illustrated by Conor McHale - the duo talk to Ray D'Arcy above.

This is a book about life and death over 8,500 years in Ireland. It explores the richness of the mortuary record that we have for Irish prehistory (8000 BC to AD 500) as a highlight of the archaeological record for that long period of time. Because we are dealing with how people coped with death, this rich and diverse record of mortuary practice is also relevant to understanding how we deal with death today, which is just as central a social issue as it always was.

Reflecting on transitional worlds: switching ancestors

Rings on her toes

Men carried the wrapped body on a bier. They were heading to the largest monument at the eastern end of the burial ground, which some said was the burial place of the person who had first come and cleared the ground here for people to live. They were followed by the village, talking about the sadness of her death for her family, but this was also a time of celebration. It was a wet morning, and the wind was bringing more rain from behind them as they slowly walked up the hill from the houses. It had been decided that rather than burning her body to free her spirit it would be better to allow her to walk after death, as she had in life. Following her journey from the grave she would meet the deceased members of her family and the ancestors.

Then they turned to the west and the children ran along the right side of the group so that the adults would protect them from the rain. All of them knew and respected her family and were glad to be part of the ceremony. Three people headed off to the north, to place offerings in the water hole that provided the village with the best water for drinking and the water that was used in ceremonies, as it was blessed by coming from ancestral grounds.

As they approached the grave they were greeted by the men who had dug it; they had made it so that it would fit her comfortably. Earth from the grave was carefully mounded up beside it. The leading elder had decided on the location. She said it would be good to place the woman on the sunny side of the family enclosure, so she would be connected and conjoined in death to her kin as she had been during her life, and would help to ensure the continuity of the family. The women lined up to take the body from the men, as it was tradition that they would bear her to the grave. Before the procession these women had washed her and dressed her. They remarked how she always liked to plunge into the water after the sweating ceremony and to look well. They had made her ready to be seen by her living relatives for the last time and to greet those who had gone before her after her journey from the grave.

When the rain cleared she was placed in the grave. Everyone gathered around to have a final look. She was laid in the grave on her right side, wearing her best clothes, with sandals carefully placed on her feet. As people felt the wet ground under their feet, they knew she would be dry shod on her journey to the Otherworld. As was the custom, they put her head to the north, close to the ancestors in the family enclosure, and placed her hands under her chin with her feet drawn up, as if she were asleep. When she woke, she would be ready to begin her journey in the direction of the setting sun, towards a new life.

To symbolise the start of her journey and her departure from this world, the women threw earth and water over her body. Then the men who had dug the grave quickly pushed the rest of the soil back over it. She was now part of the earth and had begun her journey. On the surface of the grave they placed offerings and then walked back down the hill. The talk was about the pity of her dying the way she did and when she did, and how well the ceremony had been carried out. With luck, she would find the right path, her soul would not come wandering back to upset the living and she would watch over the village like the other ancestors on the hill.

who had dug it; they had made it so that it would fit her comfortably.'

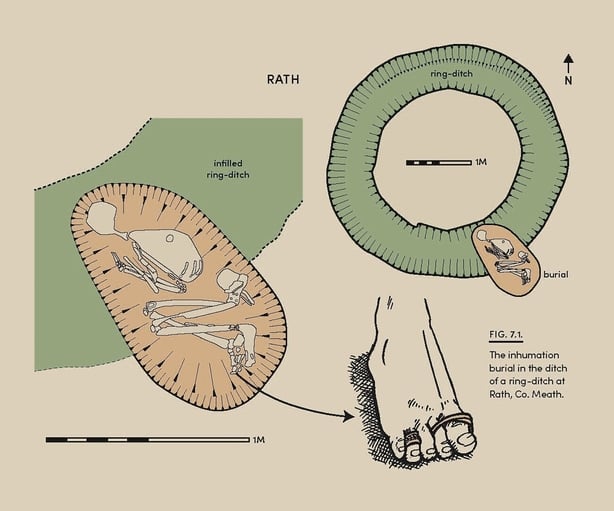

The mortuary practice at Rath, Co. Meath depicted in the fictional scenario above, with the burial of the woman inserted into the ditch of the ring-barrow with cremation deposits in the ditch itself, has a wider significance in indicating changing social mores about the role of the body after death and how it should be treated. While the bone of the woman at Rath was not suitable for dating, parallels in Britain indicate that this burial dates to the Iron Age, probably first century bc–first century ad, and is one of a number of crouched inhumations dating to the turn of the last millennium bc. In the past, the rite of extended inhumation, whereby the person is placed on their back (supine) in the grave with the head to the west, was seen as a direct reflection of the presence of Christianity. It may, however, have been adopted in Ireland before the beginnings of Christianity in the mid-fifth century ad. It might be more useful, therefore, to think of Christianisation as one of a number of interrelated changes at a time of social flux; what in wider terms would be described as the shift from late antiquity to the early medieval world. The Rath burial can be taken as a pivot point for the discussion of changes in mortuary practice.

There are a number of points to emphasise as a background. First, barrows, ring-ditches and associated practices such as flat cemeteries of pits are a major element of mortuary practice in both the later Bronze Age and Iron Age.

Second, significant changes in burial practice took place in pre-Christian times: with an increased visibility of crouched inhumation from the second century bc, as documented by the Rath burial, alongside the continued use of cremation; a subsequent wider use of inhumation as a mortuary rite in the early centuries ad, along with the use of cremation and dominance of inhumation after ad 400.

This reinforces the point above about the wider and longer-term context of social fluidity and change in which Christianisation occurred from the fifth century ad on. The context and conduit for these changes was Ireland’s position at the edge of the Celtic world and the Roman Empire.

Death in Irish Prehistory is published by the Royal Irish Academy