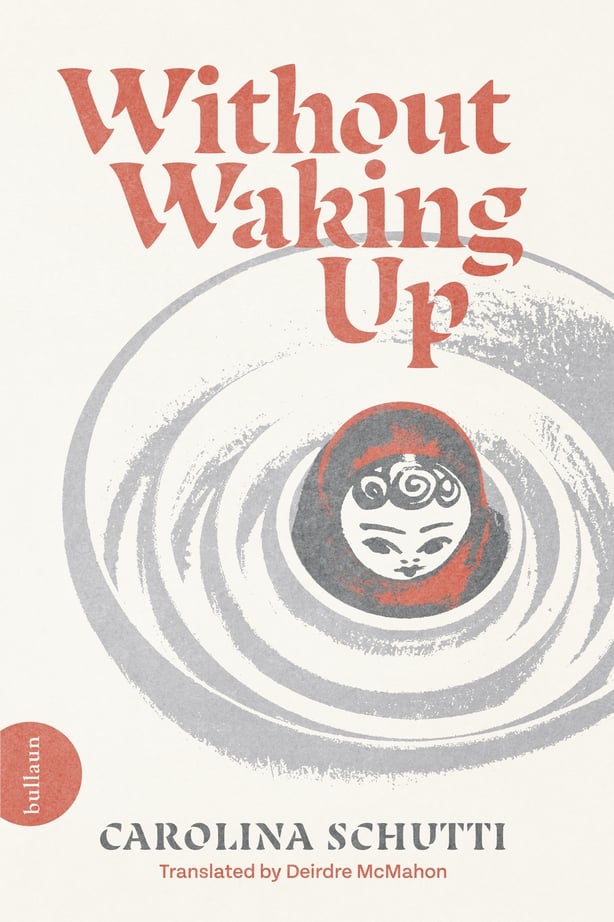

We present an extract from Without Waking Up, by Austrian author Carolina Schutti; it's the second title from new arrival on the Irish publishing scene, Bullaun Press - Ireland's first independent press dedicated to literature in translation.

Austrian author Carolina Schutti received the European Union Prize for Literature in 2015 for the original text (einmal muss ich über weiches Gras gelaufen sein), which has already been translated into 13 languages. This is the first appearance of her work in English.

Raised in an unfamiliar country by her taciturn great-aunt, Maja has brief moments of connection with her fading past through her childhood friendship with Marek, a Polish refugee with his own stories of love and loss in the face of war and displacement. Sifting through memories, simple scenes nestled into one another like her own beloved wooden doll, the Matryoshka, Maja struggles to unearth her identity. She is marked by a lingering absence – of homeland, mother tongue, mother, warmth.

Don't just stand in the doorway, she must have said; that’s what her aunt always says whenever Maja leans against the doorframe, waiting for her aunt to thrust the tea towel into her hand or point at the kitchen dresser with her chin when it is time for Maja to set the table.

It was dusky in the room; Maja had counted the little windows – adzin, dva, try – she could already count to ten but there were only three. Three little windows in thick stone walls, a wood-panelled ceiling. A lamp with a linen shade above the dining table gave out a feeble light. Her aunt turned her back to her and rattled cutlery; something was cooking on the stove. Maja didn’t recognize the smell rising from the pot and couldn’t even decide whether it was pleasant or not. She stood, rooted in the doorway, looking in turn from her father to her aunt and back again. Her father’s face was half in shadow. No one was looking at her, her aunt placed a glass of milk on the table in front of her father, then stirred the saucepan; her father was staring at the tabletop. Well then, he said. And he repeated, well. After a time that seemed endless to Maja, her aunt took a step or two towards her. Maja stood in front of the flower-patterned skirt of her apron; her aunt wiped her wet hands on it and pushed her towards the table. Maja sat down opposite her father, watching as he drank his milk. He had visited her in the children’s home; the matron led Maja to understand that he was her father and this father took her for a walk and treated her to ice cream – strawberry ice cream. When they returned to the home, Maja stood in the middle of the playroom. Strawberry ice cream, she shouted, pointing to her mouth and her dress which was flecked with pink spots. A girl stood in front of her, ran her tongue over Maja’s lips, then the screaming began, and a care worker came in looking severe and, without a word, grabbed the girl under the arms and carried her out of the room.

Sometime later the same care worker had packed a few pieces of clothing into a bag with the Matryoshka doll on top, put Maja’s shoes on her and pushed her outside the door to where her father was waiting. She had to go with him because her mother was lying under the ground and her father was going to look after her.

Maja’s aunt put a glass of warm milk in front of her, sprinkled a little cocoa powder into it, stirred it noisily and gestured for her to drink. She sat down with them, looked at Maja, then stretched out her arm and patted the child’s head.

Whatever will be, will be, she said. Her father said nothing.

The clock in the parlour strikes three; her aunt will be back in an hour. The stove is cold. The clock chimes echo, and the feeble afternoon sun makes the room seem darker than before. Maja unwraps herself from the rug and listens to see if everything is really quiet in the house, puts her two feet down together on the ground and, although she is alone, she chooses the quiet path, moving on tiptoe, to the larder. Wood creaks somewhere – the wall panelling in the hall perhaps, or the floor. Maja starts, but everything remains quiet; it was only the house. She places her hand on the door handle, hoping her aunt has not locked it. The door opens; it smells of onions and smoked sausage. Maja stands on tiptoe to reach the light switch hanging on a cord from the ceiling. The light flickers, then steadies, lighting up the shelves of the forbidden room, the room only her aunt is permitted to enter. But there’s nothing here to attract a child, just tightly sealed jars of jams, packages of sugar and flour, pots of fat, vegetables, bread that is left lying there for three days before her aunt cuts it so that they won’t eat too much. Her aunt disappeared in there after she had read her father’s last card aloud for Maja:

My Dears, Happy Easter.

Maja searches shelf by shelf, pushing a stepladder from the farthest corner of the room into the middle and feeling along the highest shelf. She feels something with sharp corners – hard, stiff cardboard. Her fingertips claw at it but she is unable to draw it towards her. Then she gets a grip on an edge of its cover, digs her fingers under the edge and, bit by bit, draws the box towards her until she can hold it in both hands. It is light, lighter than she had expected. Maja places the box on the stepladder, lifts the cover and takes out card after card. She can’t read her father’s writing although the teacher has praised her for learning her letters so quickly, more quickly than the other children, but her father’s writing spreads in great bows over the limited space on the postcards. It is like a track in the snow, looped and illegible, pressed into the cold white by fallen twigs or little heaps of snow that have fallen in thick drops from the branches. Maja holds Easter bunnies, Christmas trees and birthday cakes up to the light; she holds the written side at an angle, traces her index finger over it, breathes on it, dampens her finger with spit, wipes the moisture carefully over the card but it doesn’t reveal any secret writing – nothing had been written and then erased.

My Dears, Happy Easter.

Now Maja has to believe her aunt; a stack of punctual wishes lie in an old box without any secret compartment.

Maja puts the box back, touches the onions, sausages and bread, smells her fingers, switches off the light, closes the door and goes up the stairs to her bedroom.

Without Waking Up is published by Bullaun Press